A chimera is a plant composed of two or more genotypes in the layers that make up the shoot tip.

A common form of variegation. The leaf appears to be both green and white (or yellow). This is because the white or yellow portions of the leaf lack the green pigment chlorophyll. This can be traced back to layers in the meristem that are either genetically capable or incapable of making chlorophyll.

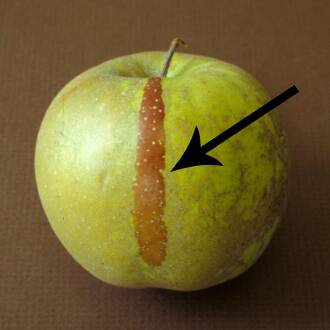

Other chimeras include alterations in the skin of fruit like color in apples or fuzziness in peaches.

Meristems are areas of active cell division and growth in the plant.

Meristems are found at the root and shoot tips (apical meristems), the edges of developing leaves (marginal meristems) and in the vascular cambium.

Cells in the meristem are characterized as being small, densely cytoplasmic with prominent nucleoli and the ability to divide.

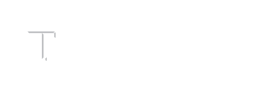

Photomicrograph of a shoot tip showing the apical meristem between two developing leaves.

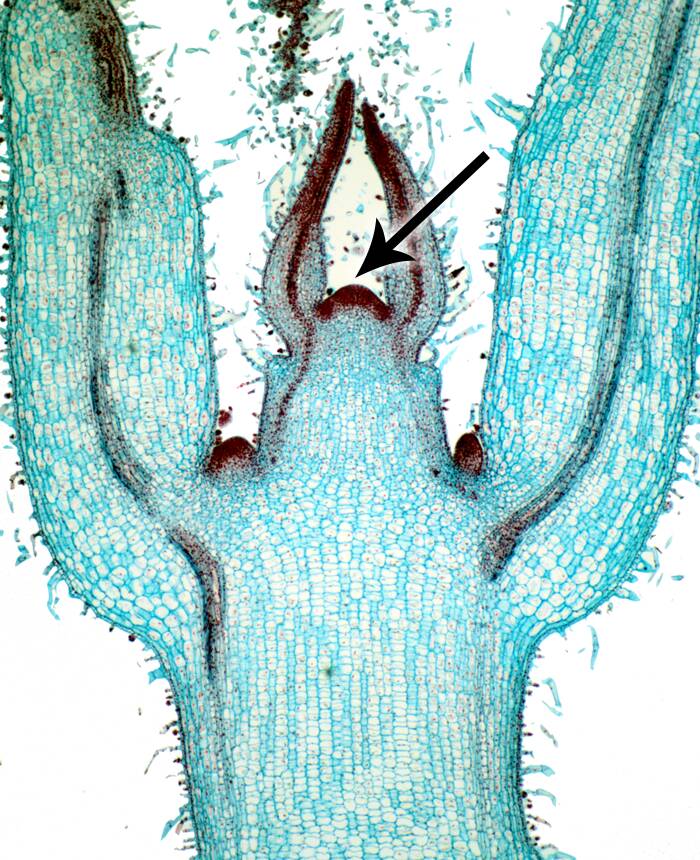

A plant's apical meristem or shoot tip is made up of relatively independent layers.

This is known as the tunica-corpus theory of meristem organization, where cell layers or tunica cover the body or corpus of the stem.

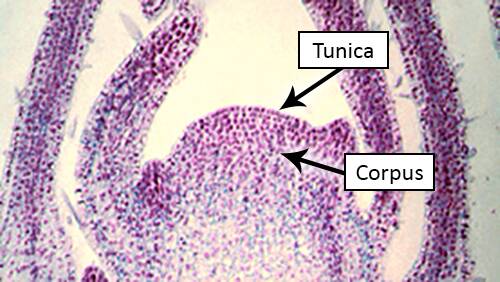

The dicot shoot meristem is usually organized into three distinct layers - LI, LII, LIII.

Typically, LI gives rise to epidermal cells. LII provides the next inner layer of cells and also the gametes. LIII cells become the inner most cells and the vascular system.

A chimera is a meristem with different genetics in one or more of the layers of the meristem.

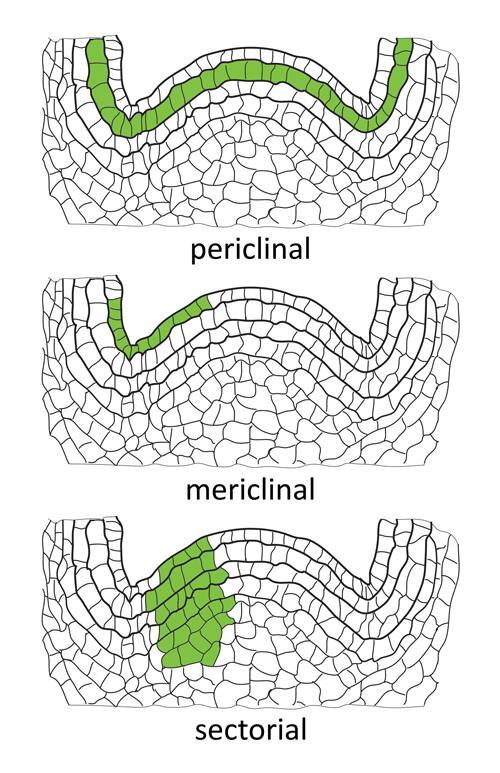

Types of chimeras include: periclinal, mericlinal, and sectorial.

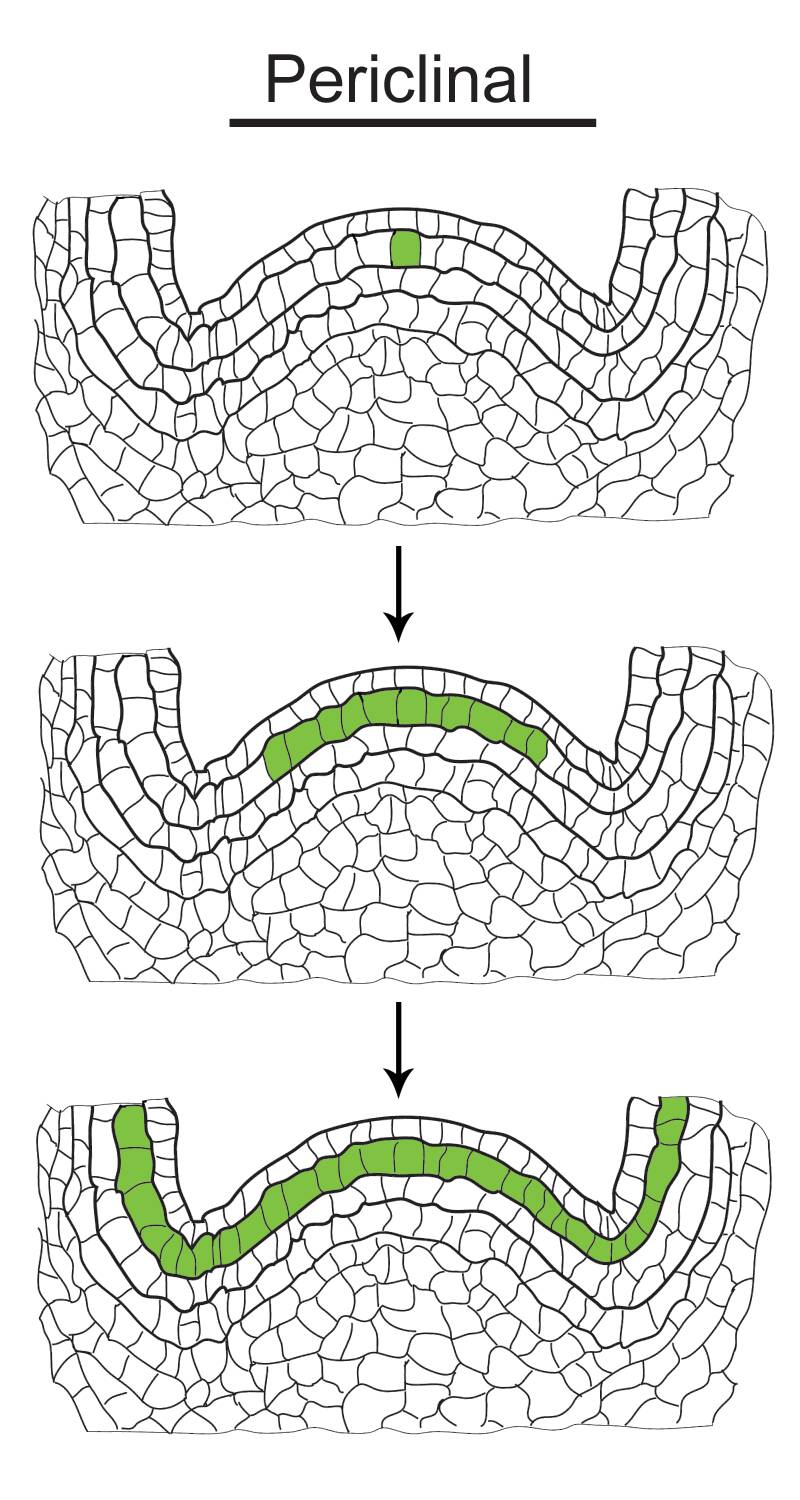

The most stable chimera type is the periclinal chimera.

In this type of chimera, one entire layer in the meristem (the LII in this example) contains the mutation.

A single cell in a layer undergoes a mutation and by anticlinal cell divisions an entire layer becomes genetically different from the other two layers.

This is a common type of chimera for variegation.

The image to the right illustrates a "sandwich" periclinal chimera where two normal layers surround a central mutated LII layer.

In this case, the LI and LIII produce cells with normal chlorophyll production while the LII does not produce chlorophyll and is colorless resulting in a variegated leaf.

The reason a colorless layer in the LII gives rise to a marginal leaf variegation is because the green LI layer that forms the epidermis covers the center of the leaf, but does not extend all the way to the leaf margin.

Along the edges, the lack of LI tissue allows the white LII layer to show through. This is the most common type of variegation pattern seen in dicot leaves.

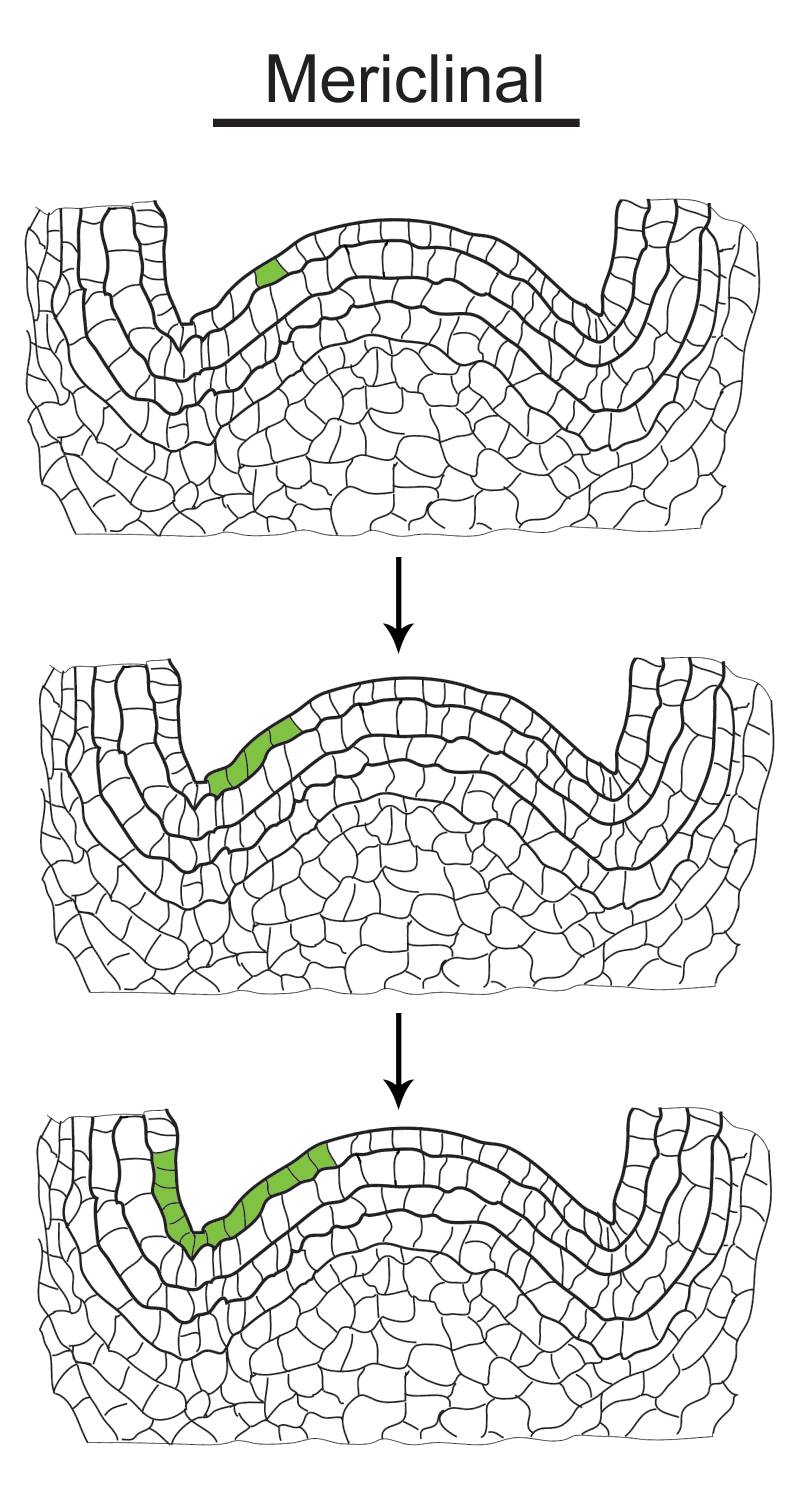

The mericlinal chimera is an unstable chimeral form.

Like the periclinal chimera, only one meristem layer contains mutant cells, but in this case they only extend across a portion of the cell layer.

This is often a transition stage where the meristem will eventually form a stable periclinal chimera or lose the mutation.

The cartoon shows that a portion of the LI layer contains the mutant cells.

In this apple, you can see that one section of the skin (epidermis – LI) has become mutated to form red pigment (anthocyanin).

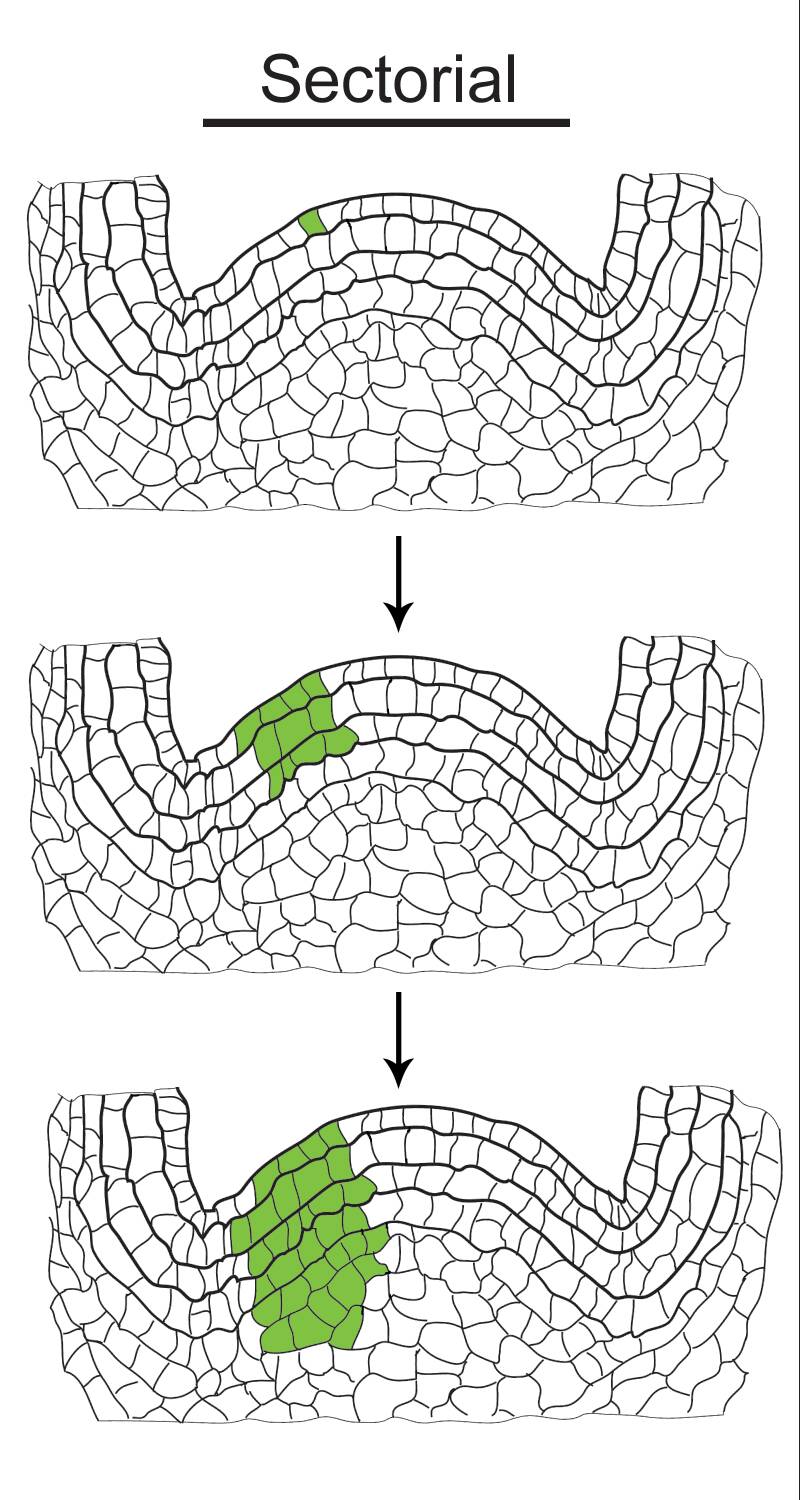

A sectorial chimera is a relatively unstable chimera type. In this chimera, on half of each layer in the meristem contains mutated cells. It is easy to see why this type of chimera is unstable.

Remember that the cells in the meristem divide by anticlinal divisions (see the cell division section for more information).

Because of this, normal cell division usually creates an all white or all pigmented meristem as the plant grows.

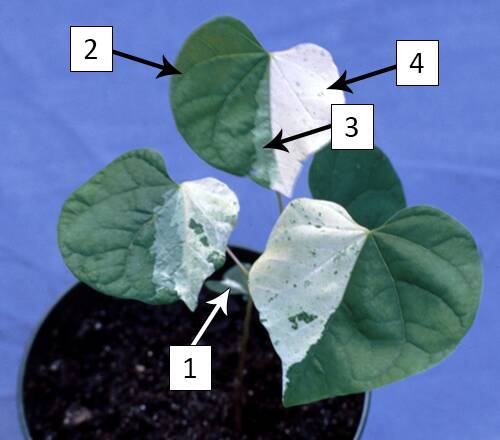

This seedling redbud (Cercis canadensis) is showing a sectorial chimera pattern. If you look closely, you can see how the pattern changes as the plant produces a new leaf.

The cotyledon shows just a single streak of white (arrow 1).

The next leaf show more of the leaf being mutated and shows the meristem layers. Arrow 2 is leaf with all layers green. Arrow 3 show the LI now without pigmentation and the LII showing through light green. The Arrow 4 indicates the all white sector.

A range of transitions states in this unstable chimera.

Plants with chimeral meristems differ in their stability. In many cases, variegated plants can show reversions to all green or all non-pigmented leaves. To maintain the chimeral variegation, these plants need to be pruned periodically to remove non-chimeral stems.

Euonymus is a relatively unstable periclinal chimera and often shows all green or all yellow stems. Since the all green stems have more chlorophyll, they can quickly grow over variegated stems.